Gardener of Eden, By Jez Abbott

Geoffrey Jellicoe was an enormous influence on Dominic Cole, so it is appropriate that he is to give this year’s Jellicoe Lecture.

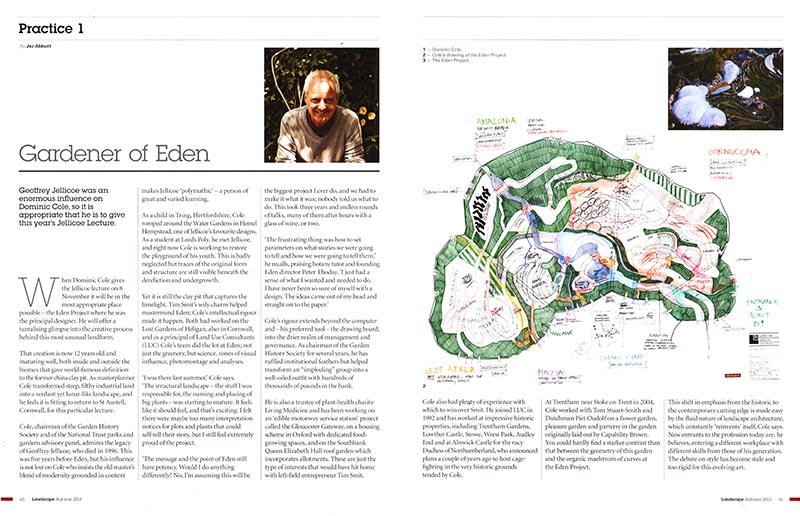

When Dominic Cole gives the Jellicoe lecture on 8 November it will be in the most appropriate place possible — the Eden Project where he was the principal designer. He will offer a tantalising glimpse into the creative process behind this most unusual landform.

That creation is now 12 years old and maturing well, both inside and outside the biomes that gave world-famous definition to the former china clay pit. As masterplanner Cole transformed steep, filthy industrial land into a verdant yet lunar-like landscape, and he feels it is fitting to return to St Austell, Cornwall, for this particular lecture.

Cole, chairman of the Garden History Society and of the National Trust parks and gardens advisory panel, admires the legacy of Geoffrey Jellicoe, who died in 1996. This was five years before Eden, but his influence is not lost on Cole who insists the old master’s blend of modernity grounded in context makes Jellicoe ‘polymathic’ — a person of great and varied learning.

As a child in Tring, Hertfordshire, Cole romped around the Water Gardens in Hemel Hempstead, one of Jellicoe’s favourite designs. As a student at Leeds Poly, he met Jellicoe, and right now Cole is working to restore the playground of his youth. This is badly neglected but traces of the original form and structure are still visible beneath the dereliction and undergrowth.

Yet it is still the clay pit that captures the limelight. Tim Smit’s wily charm helped mastermind Eden; Cole’s intellectual rigour made it happen. Both had worked on the Lost Gardens of Heligan, also in Cornwall, and as a principal of Land Use Consultants (LUC) Cole’s team did the lot at Eden; not just the greenery, but science, zones Of visual influence, photomontage and analyses.

`I was there last summer,’ Cole says. The structural landscape — the stuff I was responsible for, the naming and placing of big plants — was starting to mature. It feels like it should feel, and that’s exciting. I felt there were maybe too many interpretation notices for plots and plants that could self-tell their story, but I still feel extremely proud of the project.

`The message and the point of Eden still have potency. Would I do anything differently? No, I’m assuming this will be the biggest project I ever do, and we had to make it what it was; nobody told us what to do. This took three years and endless rounds of talks, many of them after hours with a glass of wine, or two.

`The frustrating thing was how to set parameters on what stories we were going to tell and how we were going to tell them,’ he recalls, praising botany tutor and founding Eden director Peter Thoday. ‘I just had a sense of what I wanted and needed to do.

I have never been so sure of myself with a design. The ideas came out of my head and straight on to the paper.’ Cole’s rigour extends beyond the computer and — his preferred tool — the drawing board, into the drier realm of management and governance. As chairman of the Garden History Society for several years, he has ruffled institutional feathers but helped transform an “imploding” group into a well-oiled outfit with hundreds of thousands of pounds in the bank.

He is also a trustee of plant-health charity Living Medicine and has been working on an ‘edible motorway service station’ project called the Gloucester Gateway, on a housing scheme in Oxford with dedicated food-growing spaces, and on the Southbank Queen Elizabeth Hall roof garden which incorporates allotments. These are just the type of interests that would have hit home with left-field entrepreneur Tim Smit.

Cole also had plenty of experience with which to win over Smit. He joined LUC in 1982 and has worked at impressive historic properties, including Trentham Gardens, Lowther Castle, Stowe, Wrest Park, Audley End and at Alnwick Castle for the racy Duchess of Northumberland, who announced plans a couple of years ago to host cage-fighting in the very historic grounds tended by Cole.

At Trentham near Stoke on Trent in 2004, Cole worked with Tom Stuart-Smith and Dutchman Piet Oudolf on a flower garden, pleasure garden and parterre in the garden , originally laid out by Capability Brown. You could hardly find a starker contrast than that between the geometry of this garden and the organic maelstrom of curves at the Eden Project.

This shift in emphasis from the historic to the contemporary cutting edge is made easy by the fluid nature of landscape architecture, which constantly ‘reinvents’ itself, Cole says. New entrants to the profession today are, he believes, entering a different workplace with different skills from those of his generation. The debate on style has become stale and too rigid for this evolving art.

`I get bored with the modern-versus-historic debate and don’t see myself specialising in any area,’ Cole said. ‘As a profession we are crap at explaining what we do. There’s rarely reference to the intellectual content and depth of understanding we bring to a space. It’s a fascinating but difficult conundrum; how do we explain what we do?

This strikes a raw nerve with Cole, who looks back to the golden age of Jellicoe and reckons that today’s professionals are partly to blame: ‘Landscape architects forget to celebrate what they do,’ he says. ‘There were fewer than ten when the institute was being formed after the war and they were rebuilding Britain on a megascale; power stations, housing estates, new towns.

`It was the go-to profession if you wanted to do masterplanning, and over the years we have lost that bigger picture. We have become an unseen profession and whinge about not being noticed. That’s partly because we have compartmentalised ourselves. I constantly hear expressions like green infrastructure and urban design as if they are new and separate skills.

`So tendering has become hopelessly complex involving endless services — landscape, ecology, archaeology etc. We seem to have lost the confidence to tackle a job outright under the heading of landscape architect. I see landscape architecture as an umbrella with services underneath not outside.’

Cole constantly refers to pride and passion, not just in his work but in respect of the wider profession. He is ‘passionate’ about mending schisms between designers and contractors and gardeners, and ‘proud’ that landscape architecture is not only helping to shape the modern world, but is also ensuring ‘cities, at any scale, can be liveable and sustainable’.

Article from the Landscape Institute Journal, Autumn 2013