Why memories matter

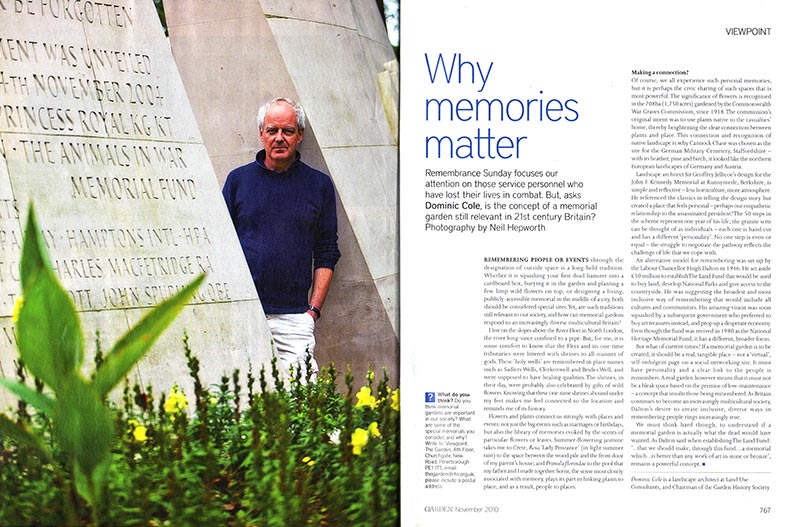

Remembrance Sunday focuses our attention on those service personnel who have lost their lives in combat. But, asks Dominic Cole, is the concept of a memorial garden still relevant in 21st century Britain? Photography by Neil Hepworth

REMEMBERING PEOPLE OR EVENTS through the designation of outside space is a long-held tradition. Whether it is squashing your first dead hamster into a cardboard box, burying it in the garden and planting a few limp wild flowers on top; or designing a living, publicly-accessible memorial in the middle of a city, both should be considered special sites.Yet, are such traditions still relevant to our society, and how can memorial gardens respond to an increasingly diverse multicultural Britain?

I live on the slopes above the River Fleet in North London, the river long-since confined to a pipe. But, for me, it is some comfort to know that the Fleet and its one-time tributaries were littered with shrines to all manner of gods. These ‘holy wells’ are remembered in place names such as Sadlers Wells, Clerkenwell and Brides Well, and were supposed to have healing qualities. The shrines, in their day, were probably also celebrated by gifts of wild flowers. Knowing that these one-time shrines abound under my feet makes me feel connected to the location and reminds me of its history.

Flowers and plants connect us strongly with places and events: not just the big events such as marriages or birthdays, but also the library of memories evoked by the scents of particular flowers or leaves. Summer-flowering jasmine takes me to Crete; Rosa ‘Lady Penzance’ (in light summer rain) to the space between the wood pile and the front door of my parent’s house; and Primula florindae to the pool that my father and I made together. Scent, the sense most closely associated with memory, plays its part in linking plants to place, and as a result, people to places.

Making a connection?

Of course, we all experience such personal memories, but it is perhaps the civic sharing of such spaces that is most powerful. The significance of flowers is recognised in the 708ha (1,750 acres) gardened by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, since 1918. The commission’s original intent was to use plants native to the casualties’ home, thereby heightening the clear connection between plants and place. This connection and recognition of native landscape is why Cannock Chase was chosen as the site for the German Military Cemetery, Staffordshire —with its heather, pine and birch, it looked like the northern European landscapes of Germany and Austria.

Landscape architect Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe’s design for the John F. Kennedy Memorial at Runnymede, Berkshire, is simple and reflective — less horticulture, more atmosphere. He referenced the classics in telling the design story but created a place that feels personal — perhaps our empathetic relationship to the assassinated president? The 50 steps in the scheme represent one year of his life; the granite setts can be thought of as individuals — each one is hand cut and has a different ‘personality’. No one step is even or equal — the struggle to negotiate the pathway reflects the challenge of life that we cope with.

An alternative model for remembering was set up by the Labour Chancellor Hugh Dalton in 1946. He set aside £50 million to establishThe land Fund that would be used to buy land, develop National Parks and give access to the countryside. He was suggesting the broadest and most inclusive way of remembering that would include all cultures and communities. His amazing vision was soon squashed by a subsequent government who preferred to buy art treasures instead, and prop up a desperate economy. Even though the fund was revived in 1980 as the National Heritage Memorial Fund, it has a different, broader focus.

But what of current times? If a memorial garden is to be created, it should be a real, tangible place — not a ‘virtual’, self-indulgent page on a social networking site. It must have personality and a clear link to the people it remembers. A real garden however means that it must not be a bleak space based on the premise of low-maintenance — a concept that insults those being remembered. As Britain continues to become an increasingly multicultural society, Dalton’s desire to create inclusive, diverse ways in remembering people rings increasingly true.

We must think hard though, to understand if a memorial garden is actually what the dead would have wanted. As Dalton said when establishing The Land Fund: ‘…that we should make, through this fund….a memorial which…is better than any work of art in stone or bronze’, remains a powerful concept.